Providing the precepts of Universal Design to classrooms and teaching methods can provide students an education that is truly fair for all.

Several CHC faculty and staff members joined their peers from four other local institutions at Haverford College January 16 for the first of four workshops scheduled this semester around the topic of “Access to Learning.”

This initial workshop attracted participants from Bryn Mawr, Swarthmore, Haverford and Chestnut Hill colleges and Temple University, and presenter Rebecca Cory, Ph.D., an associate professor from the City University of Seattle. Dr. Cory edited the book “Universal Design of Higher Education: From Principles to Practice,” and is an expert on the concept as well as a professor and researcher.

“Universal Design is a paradigm, or framework, for how to start thinking about how to design courses and programs to make them better for all students,” said Cory.

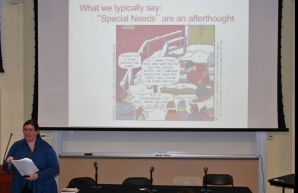

She shared a popular cartoon that shows a line of animals standing near a tree — a bird, monkey, penguin, elephant, a fish in a bowl, seal and a dog. The instructor sitting behind a desk says, For a fair selection, everybody has to take the same exam. Please climb that tree.

“Fair and equal are not necessarily the same thing,” she continued. “Being fair is giving every student what they need, not the same things. And ‘special needs’ students are often an afterthought.”

She said that college campuses are designed to fit “typical students,” and add “accommodations” for those who don’t fit the mold. “Universal Design equals an inclusive environment — a design for the greatest diversity of students. We must imagine every potential type of student and design for them all.”

She shared a brief video that explained how Universal Design minimizes barriers and maximizes learning for all students by remembering that the way people learn is as unique as their fingerprints. Everyone approaches learning from a different background, with different strengths and interests.

She suggested changing the perception of what are commonly called “accommodations,” and instead refer to them as “resources,” and one way to begin that change is to discover the biggest barriers to learning for all students.

Cory confirmed that the trend toward having an increased number of students needing special accommodations is a national one. Students require these accommodations — academic/residential/dining — because of physical, mental or emotional disabilities, differences in learning styles and even because of chronic medical conditions.

Accommodations can be long-term, such as ramps, provision of note-takers in class or special testing rooms or changes made to food served in the dining hall because of dietary considerations. Or modifications can be temporary, if someone has a concussion or broken bone, for example.

The framework for Universal Design is simple. Use multiple means of representation to ensure that everything is understood and have the desired effect for everyone. For example, present a lesson using pictures, words, speak it aloud and send electronic files before class. Students need to be able to express themselves and learn in the manner which is most appropriate to their learning style.

Keely McCarthy, Ph.D., associate professor of English and coordinator of the writing program believes that the idea that classrooms should be made accessible is obvious, however, the means of doing that is challenging.

“My goal is for all of the first-year CHC writing classes to integrate Universal Design into their classes within five years,” she said after the presentation, adding her first step was to modify the attendance policy, which is now more flexible, but puts more responsibility on the student. She also has been working on the way documents are designed.

“The most difficult aspect to change is the way we teach and the activities we do in the classroom. I would like to look for outside funds to help us have the time and money to train faculty to rethink their pedagogy within this model. I hope that our work on that can help other faculty see ways to make that happen in their own classes,” she added.

Cory stressed the importance of thinking beyond the need of the individual. “The ideal is to extend the same services to all students. If a ramp is built for access to a building, those who have no trouble walking can use it as well as someone who uses a wheelchair.”

According to Kristin Tracy, director of the Disability Resource Center, 94 CHC students are registered with her office, although not all students use accommodations all the time.

“By the end of last semester there were 52 students actively using accommodations,” she said, although the number can vary throughout the semester. “Not all of them use accommodations throughout their entire academic career, however. For example, a student with a math disability may need accommodations for a math class, but not for any other course.”

Tracy believes in the concept of Universal Design for its ability to put all students onto equal ground.

“I think it’s great that CHC is taking an active role in learning how to create accessible courses,” she says. “Although it’s a relatively easy thing to do, it takes creative thinking and trial and error to get there.”

Visit www.cast.org for more information about Universal Design principles.

The subsequent workshops will focus on ADHD in February, teaching non-English speakers in March and the autism spectrum in April.