Through a series of fortuitous events, Marie Conn Ph.D., professor of religious studies, learned about the CANDLES Holocaust Museum in Indiana two years ago. After visiting the museum’s website, Conn connected with its founder, Eva Kor. Kor founded CANDLES — Children of Auschwitz Nazi Deadly Lab Experiments Survivors — in 1984 as a way to shed light on this dark chapter of the Holocaust and to honor her twin sister who had died the year before.

In addition to education, the museum’s mission has grown to include an advocacy for the importance of respect, equality, peace and the value of forgiveness.

When Eva and her sister, Miriam, were 10, they and their two older sisters and parents were transported to Auschwitz. Miriam and Eva were the only survivors, and they suffered through the inhuman experiments performed on twins by Dr. Josef Mengele. The sisters nearly died, but they survived together and were liberated on January 27, 1945.

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of the camp’s liberation and to honor both those who had survived and those who did not, Kor led a group from Indiana to Auschwitz in January. Conn joined them, and the following is an excerpt from the journal she kept during her visit in January.

* * *

On a frigid January 27, 1945, Soviet troops liberated Auschwitz and Berkinau, the infamous death camps set up by the Nazis in southern Poland. On a frigid January 27, 2015, some 70 of us have the privilege of accompanying survivor, Eva Kor, to the ceremony at Berkinau. With her twin sister Miriam, Eva spent nearly a year enduring the experiments conducted by Dr. Mengele, a Nazi scientist intent on finding a way to use genetics to create “pure” Aryan babies.

As our buses leave Krakov for the hour-long drive to the camps, we ride through a countryside made beautiful by recent snowfalls. The beauty and peace outside our windows belie the history into which we immerse ourselves.

Security is surprisingly simple and the guards quite friendly. The snow is still falling, adding an extra layer of beauty and peace to the surroundings. We are the first group to arrive, so we walk nearly the length of the camp to our space right in front of a big screen. (We could not enter through the iconic gate with the railroad tracks. Those of you who saw this on TV know why—the huge tent was actually installed over that gate.)

That was it for us for the day — standing in front of the screen, employing whatever tricks we could think of to stay, not warm, but nearly bearably frigid. We think of 10-year-old Eva and Miriam and all the others who had very little clothing (and even less heat) who walked where we now stand. Steven Spielberg had produced a new 15-minute documentary which was played on the screen about every hour. At some point, the camera in the tent comes on and we watch that tent fill up.

The ceremony itself is mostly music and speeches, most in Polish with no translation, since everyone inside the tent has earphones. When that part is over, the dignitaries and a few survivors walk or ride to the memorial at the other end of the camp and place lighted candles in front of the various plaques. By now it is very dark so this is impressive.

Birkenau is actually Auschwitz II, built when Auschwitz I was no longer large enough. There is also an Auschwitz III, which was a labor camp. Birkenau — built by the inmates of Auschwitz — is huge; it became a factory of death, a killing machine. Stanley Kalmanovitz, a former prisoner of Auschwitz-Birkenau who is spending the week with us, spent some time in Auschwitz and remembers being part of those work details. Where the buildings in Auschwitz I are brick and all originals, those in Birkenau are mostly wood, so most of those standing are reconstructions. The site was chosen to be near the railroad tracks, which you can see in the iconic photos of the main gate. Railroad cars arrived every day. The selection platform was outside the gates (by Eva’s time, it had been moved inside). As the prisoners stepped out of the cars, they were divided into left (able-bodied; would live, at least temporarily); and right (elderly, children, sick; were marched directly to the gas chambers).

In Birkenau, we see the building that was Eva’s and Miriam’s home for 10 months, as well as the building where Dr. Mengele drew their blood. Three times a week, all the twins were marched to Auschwitz (How did they ever walk all that way, especially with what was being done to them?) where all the testing was done. We walk through only a small percentage of the camp and are tired out. At the end of the main road, next to the remains of one of the bombed-out crematoria, is the memorial to all those who died in the Holocaust.

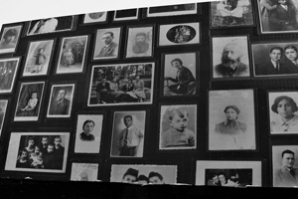

The “Sauna,” a building at the far end of the camp, is where the condemned were prepared for the gas chamber. It’s been refurbished, and in the main entrance, there is one of the most poignant of many poignant displays: hundreds of photographs found in the belongings of the condemned. Photos of people laughing, singing, enjoying vacations and family moments, weddings and so on. The Jews were told to bring a suitcase with their valuables, and to label each case carefully so that they could retrieve it “when they left.” Even after they had been stripped and shaved, they were told to put their clothes on a numbered peg for easy retrieval. Then they entered the next room and never came out. Stan tells us that, after he was liberated, the first time he tried to take a shower was traumatic; he was afraid it wouldn’t be water that came out.

Eva’s candle ritual of remembrance and forgiveness usually takes place at the Execution Wall in Auschwitz. Because of the different schedule this time, we gather at the Memorial at Birkenau. Eva lights a candle and forgives all who had caused her pain. Each of us lights a candle to place at the memorial, and anyone who wants to is invited to say something. I light mine in loving memory of my parents, Alice and Ira, and in honor of the grandparents I never knew, Ukrainian Jews who fled the pogroms and made my life possible.

Auschwitz I, although large, is not nearly as large or widespread. It was not built to be a concentration camp. It had been a Polish Army installation. When the Germans occupied southern Poland, they took it over. The buildings are all brick with red tile roofs. There are trees and greenery and, in a surreal way, walking around feels like wandering the campus of an Ivy League college. Of course, all one has to do is walk inside any building to realize the horrible difference.

Inside Building 21 there is a stunning exhibition. The first floor illustrates Jewish life in Europe (not just Poland) before the war; the scenes of ordinary people doing ordinary things — dancing, swimming, ice skating, processing with the Torah, playing and so on — before the implementation of the “Final Solution” — are heart-breaking. You can’t help but smile at the images as they move past you, but you know what those people didn’t about the fate that awaited them. The second floor is about the Holocaust, with videotaped testimonies from survivors. The next room seems empty until you look closely at the walls. There are pictures drawn by the children and they break your heart. (There are wonderful drawings in the children’s building in Birkenau also.) The final room contains a book that is hard to describe. The pages are huge and are set up vertically — hundreds of pages filled from top to bottom with close-written names — a directory of victims. When CHC graduate student, Hannah Brown, and I traveled with Eva in 2013, someone found Eva’s family. As you leave this room to exit, there are several small screens on the wall flashing snapshots of survivors and their friends and family — a note of stubborn hope in the aftermath of such tragedy.

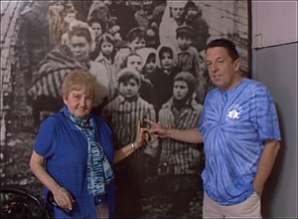

We each have a photo taken with Eva in Building 6, where there is a large copy of the liberation photo that shows Eva and Miriam at the head of the children being led out. Most of the children refused to wear the striped prison coats they were offered, but both she and Miriam are wearing them. Eva is very practical, and she wanted the extra layer for warmth — remember that liberation took place in late January.

Building 11 was the punishment and execution building. Moving past the various punishment rooms — starvation, suffocation, standing — is almost too much to take. One of the rooms has a small memorial to Maximilian Kolbe. Another building that is really emotionally draining is the one that has huge collections of “stuff” — the ordinary stuff of ordinary people — eyeglasses, shoes, brushes, baby clothes, suitcases and hair. All these things were sent to headquarters and were used for all sorts of manufacturing.

Sensing their impending defeat, the Nazis bombed the four crematoria at Birkenau. The one at Auschwitz has been reconstructed using original material. It is our final stop, and most of us need a period of quiet reflection on exiting. It is almost too real.

Many years ago, camping through Europe with a friend, I had the chance to visit Dachau, the concentration camp outside Munich. The survivors had commissioned a sculpture with the dates on one side and on the other the challenge, in three languages, “Never Again!” How sad that their challenge has been met by silence, for it has happened again and again and again.

May we all work so that one day their prayer will be answered.

ED. NOTE: In 2013, Patrick Fazio, then a TV news anchor in Terre Haute, Ind., was part of the same group as Marie Conn. He produced five segments about Eva Kor and her pilgrimages to Auschwitz and her mission of education and forgiveness. The resulting video is quite moving and can be seen on YouTube, here.

—Marie Conn, Ph.D.